Union Find Algorithm Part I

Earlier this summer, I tried to balance an algorithms course and my bootcamp workload. I chose Princeton’s Algorithms Part I with Robert Sedgewick and Kevin Wayne, which can be found on Coursera. Ultimately, that turned out to be too much to balance, but before I dropped the algorithms course I watched the videos on Union Find. This blog post (and Part II) works through the code presented in those lectures (originally written in Java, but I’ve written it out in Javascript for my own comfort).

The Union Find algorithm (also called Disjoint Set) finds or creates a connection between two objects. When considering the problem, we can look at the connections in a few different ways:

- reflexive: p is connected to p

- symmetric: if p is connected to q then q is connected to p

- transitive: if p is connected to q and q is connected to r, then p is connected to r

This algorithm has two parts: the find query and the union query. The find query checks if two objects are in the same group, whereas the union query joins two objects that are not already in the same group.

There are different ways to approach this problem and I will cover two solutions in this post and follow up with the ideal solution in Part II.

Quick Find

Below, I’ve created a class “QuickFind” which is initialized with an array (named “ids”) of objects of size num. Each object in “ids” begins as its own group, with their initial group ID being its own index. The class contains class methods “connected” and “union.” The connected method checks if the objects at indexes p and q are in the same group by checking if they point to the same group ID in “ids.” The union method joins two objects by changing all the group ids that match ids[p] to the group ID of ids[q].

class QuickFind {

// build an array of num length

constructor(num) {

this.ids = [];

for (let i = 0; i < num; i++){

this.ids.push(i)

}

}

// checks whether p and q are in the same component

connected = (p, q) => {

return this.ids[p] === this.ids[q];

}

// changes all entries with ids[p] to ids[q]

union = (p, q) => {

let pids = this.ids[p];

let qids = this.ids[q];

for (let i = 0; i < this.ids.length; i++){

if (this.ids[i] === pids) {

this.ids[i] = qids;

}

}

}

}

let newIds = new QuickFind(10)

// the original array

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

// create a union

newIds.union(2, 5)

// 2's ID was changed to 5, showing that they're in the same group

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

// check if 7 and 5 are connected

newIds.connected(7, 5)

// false

newIds.union(7, 2)

// 7's ID was changed to 5 to join the group

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 5, 8, 9]

// 7 and 5 are now connected

newIds.connected(7, 5)

// true

newIds.union(2, 8)

// 2, 5, and 7 all changed their IDs to 8

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 8, 3, 4, 8, 6, 8, 8, 9]

// 5 and 8 are now connected

newIds.connected(5, 8)

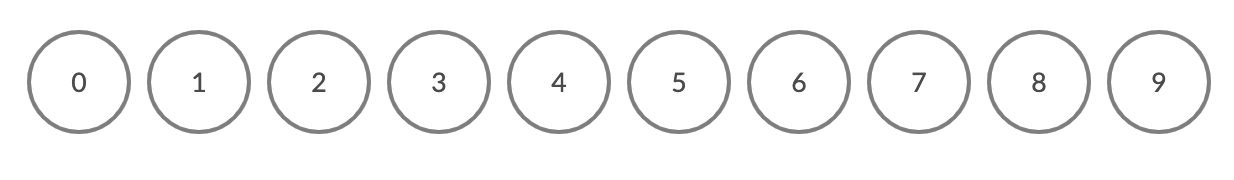

// trueTo further cement this concept, I decided to create some visuals with the app “Creately.” Below, I’ve represented an array of 10 objects in which each object is initialized with its own group ID, here their index number.

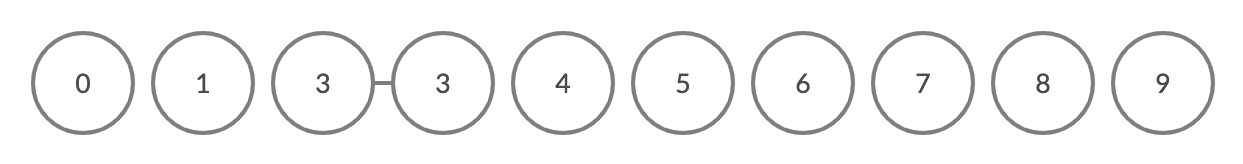

If we create a union between 2 and 3, the group id of 2 is changed to 3.

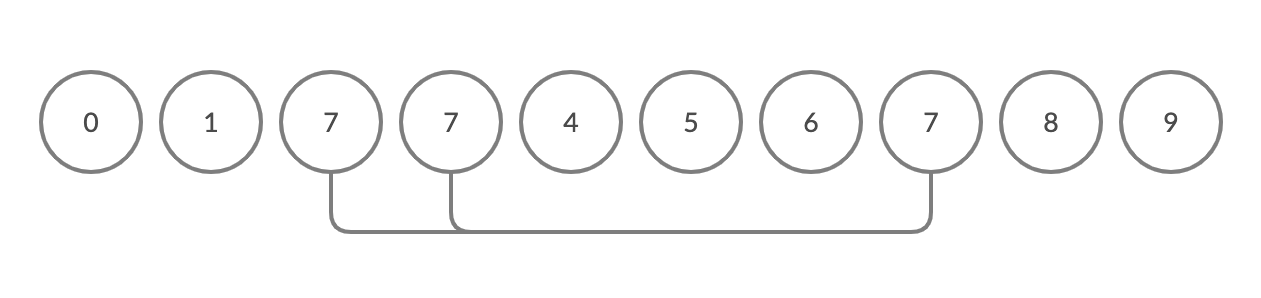

When a union is created between 3 and 7 all objects that match the group ID of ids[3] are changed to have the group ID of ids[7].

Unfortunately, this is not the most efficient way to approach this problem. The downside is that the union command is too slow because it loops through the entire array for each union operation.

Quick Union

A moderate improvement on Quick Find is Quick Union. The QuickUnion class is also initialized with an array “ids” of size num and has class methods “connected” and “union.” The key difference with this solution is how we represent the groups of joined objects. They are represented hierarchically, similar to a tree. Instead of all the objects of the same group having the same group ID, each object points to its parent until the root object is reached (the root points to itself).

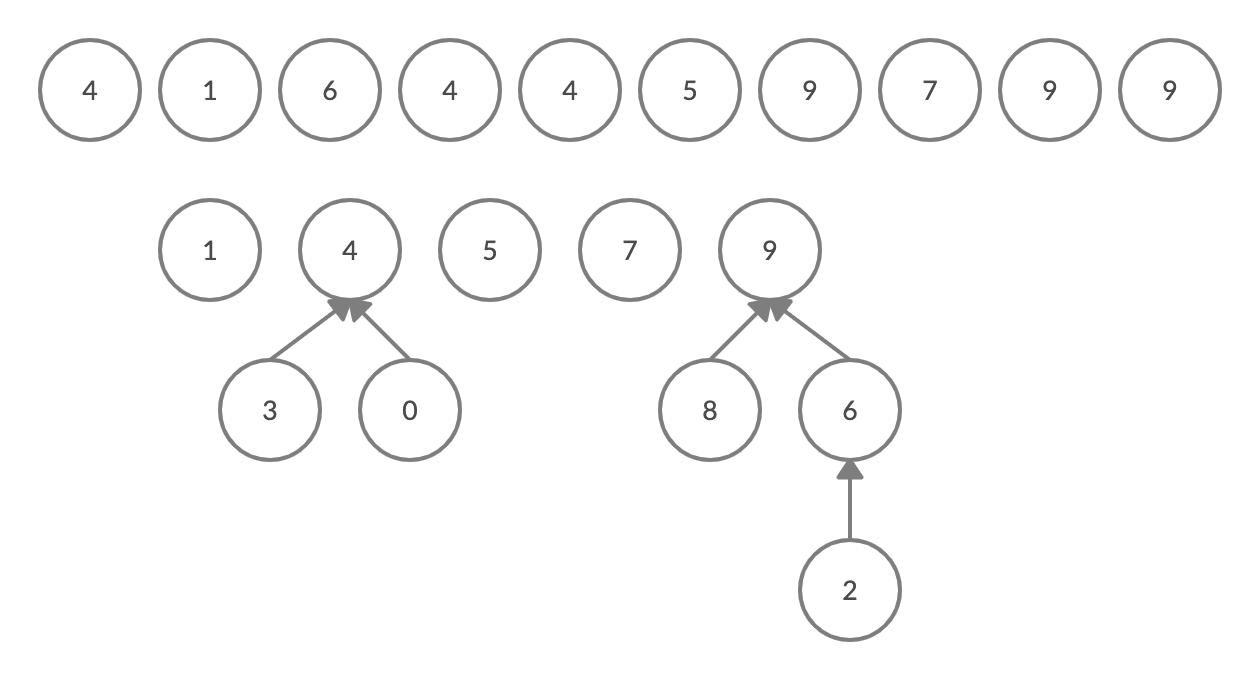

For example, in the image below there are 2 multi-object components ([0, 3, 4] and [2, 6, 8, 9]) and 3 single object components (1, 5, 7). If you follow the second larger tree beginning at 2, you are pointed to its parent 6, then to 9, which is the root. While it’s easier to visualize with the tree structures on the bottom, you can accomplish the same thing with the array on top. If you go to ids[2] you are pointed to ids[6], and then ids[9] where the trail ends.

Parts of the QuickUnion class are similar to QuickFind, but the addition and use of the findRoot method reflects QuickUnion’s different approach to the problem. This method finds and returns the root of a tree at a given index. The root is where ids[i] is the same as the index i. The connected method uses findRoot to check if p and q are in the same component and the union method uses findRoot to join p and q by changing p’s root to be the child of the root of q.

class QuickUnion {

// build an array of num length

constructor(num) {

this.ids = [];

for (let i = 0; i < num; i++){

this.ids.push(i)

}

}

// root is where ids[i] is same as index

findRoot = (i) => {

while (i !== this.ids[i]) {

i = this.ids[i];

}

return i;

}

// checks whether p and q are in the same component

// by checking to see if they have the same root

connected = (p, q) => {

return this.findRoot(p) === this.findRoot(q);

}

// connects p and q by making the root of p

// have the root of q as its parent

union = (p, q) => {

let i = this.findRoot(p);

let j = this.findRoot(q);

this.ids[i] = j;

}

}

let newIds = new QuickUnion(10)

// original array

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

// 2 and 5 are not connected

newIds.connected(2, 5)

// false

newIds.union(2, 5)

// 2 now points to its parent 5, showing they are joined

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

newIds.union(7, 2)

// 7 now points to 5 because 2's root is 5

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 5, 8, 9]

newIds.union(2, 8)

// while 2 still points to 5, 2's root(5)

// now has as its parent 8's root(8). 5 points to 8

newIds.ids

// [0, 1, 5, 3, 4, 8, 6, 5, 8, 9]

// 2 points to 5, 5 points to 8, 8 points to itself

newIds.findRoot(2)

// 8This isn’t the most efficient solution, either, as the trees can get too tall. The union method is quicker than in QuickFind because it doesn’t loop over the entire array. In QuickFind it goes through the whole array, accessing it N times, whereas in QuickUnion the findRoot method used in “union” only traverses the height of the tree. It can be improved in a couple different ways, but I’m not going to cover that here. Stay tuned for those improvements in Part II!

Working through the lessons and videos about this algorithm was difficult for me. It’s been a while since I worked with higher-level math and wrapping my brain around the efficiency of these solutions and their logic took a long time. It helped to go through the solutions on CodePen and create visuals to better understand each improvement.

Source: Princeton University, Algorithms Part I, taught by Robert Sedgewick and Kevin Wayne